Dancing to Death

(2 reviews)

| Published In: | 2011 |

|---|---|

| ISBN: | 978-99936-835-0-6 |

| Category: | |

| No. of Pages: | 72 |

Nu. 300.00

Book Overview

If you have ever listened to Leonard Cohen or Tom Waits or Bob Dylan, if you have ever read Murakamiʼs fiction, if you have watched movies by French auteurs or Bergman or Wong Kar-Wai, if you have delighted in the verses of Blake, Whitman, Yeats, Rimbaud, Celan, Carver, Rich, or The Beats -- you will cherish these poems.

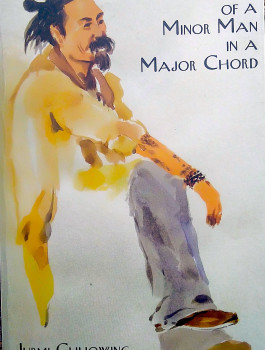

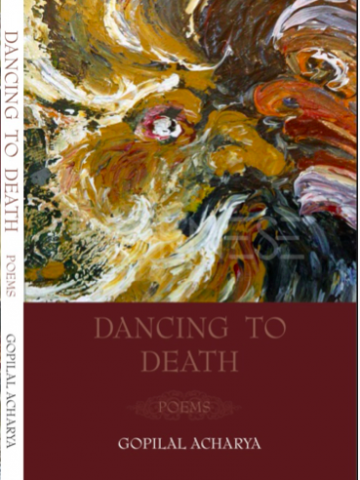

Dancing to Death, a hauntingly beautiful collection of recently published poems by Gopilal Acharya, an accomplished Bhutanese editor and writer, is a verse-memoir of love, death, and perhaps, the death of love. There are 49 poems in the 72 pages of the book, which has as its cover, paintings by the acclaimed Bhutanese artist Kama Wangdi.

We suffer to narrate the pleasures of our pains. And the worthy verses here are stunning in their ability to convert the poetʼs pain into our pleasure. Do read!

(Excerpt from a review by Prof. Nitasha Kaul, Westminster University, UK)

Write a Review

Customer Reviews (2)

The two poetry collections I often come back to are Gopilal Acharya’s Dancing to Death and the great Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer’s The Half-finished Heaven. I re-read these poets for several reasons. First, they are both brief and tell what they need to with as little embellishment of the language as can be possible. Brevity, I think, is a sign of knowledge; someone who knows his topic can talk about it in brief while touching sufficient depth. Second, both these books are slim. Third, they are both beautifully designed. The design definitely adds to the pleasure of reading. Fourth, both the poets touch what we call the human condition with quite a casual ease. Here I’ll talk only about the aspects of Acharya’s poems. I am writing a note on Dancing to Death after all.

This book is almost autobiographical. But autobiography not necessarily of the author but of any person (man or woman) who is asking of the self some fundamental questions. The poems speak for a sensitive person who is confused, and every sensitive person always is. I have this image for the poems: a person is facing a host of answers, arrayed in a single file like criminals at a firing squad, for his question. His method of choosing the right answer is by shooting arrows at them. One answer is caught by the arrow, but that’s not the answer. Second…that isn’t either…third…fourth… nth…not one’s the answer. The options are empty themselves, as the questioner is. All the options die. They are alone, the question and the questioner. "I asked the question/And the question asked me".

But the question looks beyond the questioner; it looks at history itself. The poet, however, doesn’t bring history to suffer at the witness stand; he merely lets us know that history had always been here, pursuing us at our heels. "But the darkness was here always/and probably that distant beauty too/just the history went unwritten/and unnoticed in this part of the world". The title poem, from which the preceding excerpt is taken, possesses a quaint beauty; a man is propped up into life by the questions he has. Unanswered though they are, these questions make up the totality a person is. That I think is the unifying theme in this collection, though there are other themes, too.

For the poet, love, music, death (all of which are anchored on the formidable wharf of alcohol) are the prime movers of life as is presented in the collection. These give rise to the essential questions. Whether you are in love or out of it, whether it is love realised or thwarted, it has the ability to touch the subterranean details of history and existentialism. Death is another force the poet places adjacent to love. These two represent polarities, but with a bit of help from alcohol, these two can very well sit at a table, almost dating. This cuts a comic image, but it presents other folds at the same time. This duality is inescapable. The guys with the philosophies will tell you so, too.

Carver, Jazz, Byron, Dylan, and alcohol — this maddening congregation lurks about conspiringly in the poems. If you have read your Murakami like the poet has read his, you’d find another man who can create situations, confusions, and dilemmas and call in whispering allusions to the greats and the commons in the way of the great Japanese.

The collection with 49 poems covering about 70 pages has rich wealth in it. The poems ask dangerously infectious questions — they could infect and leave you questioning yourself. The poet presents life in its full complexity. You are being questioned so thoroughly that the question and its subject almost lose identity and merge. You become the question: historical, existential, and spiritual. You are not in for that sort of philosophical innuendos? The sheer lyricism of the poems itself does a sufficient job expected of poems. The casual ease with which the poet writes is evident in the fact that you will never have to run to a dictionary. The words are everyday words. The wide range of possibilities the arrangement of common words creates is unsettling to me.

I have mentioned the poet asks many fundamental questions. But if you are expecting to find answers, too, then you should lower your expectations. The poems leave you confused, the same way life does; but in the end, you have more questions and probably fewer answers. What Byron does to the poet, the poet does to me ("after 30 minutes of reading Byron/Byron leaves me more confused). After every reading, this poet leaves me confused, too. This confusion is a part of life. We ask questions, the questions, ever the more persistent, ask us back and turn us into questions. These strict bargains we pursue in life betray "a chink of clarity". These are what we call experiences. The poems are about such events or are events themselves.

I love this book. You’ll, too.

This book is almost autobiographical. But autobiography not necessarily of the author but of any person (man or woman) who is asking of the self some fundamental questions. The poems speak for a sensitive person who is confused, and every sensitive person always is. I have this image for the poems: a person is facing a host of answers, arrayed in a single file like criminals at a firing squad, for his question. His method of choosing the right answer is by shooting arrows at them. One answer is caught by the arrow, but that’s not the answer. Second…that isn’t either…third…fourth… nth…not one’s the answer. The options are empty themselves, as the questioner is. All the options die. They are alone, the question and the questioner. "I asked the question/And the question asked me".

But the question looks beyond the questioner; it looks at history itself. The poet, however, doesn’t bring history to suffer at the witness stand; he merely lets us know that history had always been here, pursuing us at our heels. "But the darkness was here always/and probably that distant beauty too/just the history went unwritten/and unnoticed in this part of the world". The title poem, from which the preceding excerpt is taken, possesses a quaint beauty; a man is propped up into life by the questions he has. Unanswered though they are, these questions make up the totality a person is. That I think is the unifying theme in this collection, though there are other themes, too.

For the poet, love, music, death (all of which are anchored on the formidable wharf of alcohol) are the prime movers of life as is presented in the collection. These give rise to the essential questions. Whether you are in love or out of it, whether it is love realised or thwarted, it has the ability to touch the subterranean details of history and existentialism. Death is another force the poet places adjacent to love. These two represent polarities, but with a bit of help from alcohol, these two can very well sit at a table, almost dating. This cuts a comic image, but it presents other folds at the same time. This duality is inescapable. The guys with the philosophies will tell you so, too.

Carver, Jazz, Byron, Dylan, and alcohol — this maddening congregation lurks about conspiringly in the poems. If you have read your Murakami like the poet has read his, you’d find another man who can create situations, confusions, and dilemmas and call in whispering allusions to the greats and the commons in the way of the great Japanese.

The collection with 49 poems covering about 70 pages has rich wealth in it. The poems ask dangerously infectious questions — they could infect and leave you questioning yourself. The poet presents life in its full complexity. You are being questioned so thoroughly that the question and its subject almost lose identity and merge. You become the question: historical, existential, and spiritual. You are not in for that sort of philosophical innuendos? The sheer lyricism of the poems itself does a sufficient job expected of poems. The casual ease with which the poet writes is evident in the fact that you will never have to run to a dictionary. The words are everyday words. The wide range of possibilities the arrangement of common words creates is unsettling to me.

I have mentioned the poet asks many fundamental questions. But if you are expecting to find answers, too, then you should lower your expectations. The poems leave you confused, the same way life does; but in the end, you have more questions and probably fewer answers. What Byron does to the poet, the poet does to me ("after 30 minutes of reading Byron/Byron leaves me more confused). After every reading, this poet leaves me confused, too. This confusion is a part of life. We ask questions, the questions, ever the more persistent, ask us back and turn us into questions. These strict bargains we pursue in life betray "a chink of clarity". These are what we call experiences. The poems are about such events or are events themselves.

I love this book. You’ll, too.

One of the prolific writers from Bhutan. Dancing to Death is the reason why we need poetry.